Founded in 1980 |

|

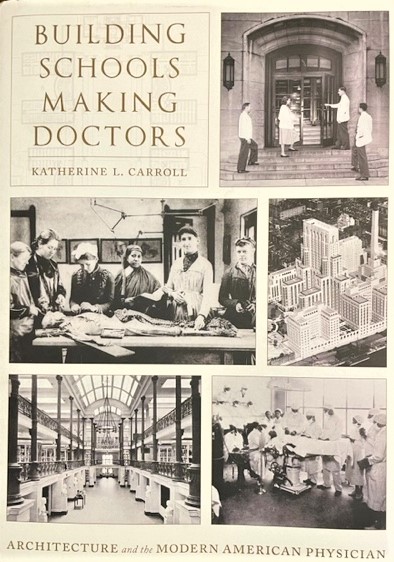

| Katherine L. Carroll, Building Schools Making Doctors: Architecture and the Modern American Physician, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022. ISBN 978-0-8229-4705-9 |

Reviewed by: Alan J. Lippman, MD

April 24, 2023

In architecture, the maxim “Form follows function” is attributed to Louis Sullivan, the early twentieth-century American architect known for pioneering modern building design principles. In this sense, as Sullivan represented, the shape and organization of a building should relate to its intended function or purpose.

This principle was highlighted in a recent article in the New York Times1 that explored the challenges of converting office buildings into apartments. This process, intended to reconfigure structures originally intended for commercial purposes into residential spaces, is a consequence of changing economic realities and illustrates the importance of building design to promote appropriate functionality.

How this process of building design relates to medical education is the subject of Katherine Carroll’s unprecedented study, focusing on the evolution of medical school design between 1893 and 1940. During this period, many medical colleges built or rebuilt their facilities to meet the changing needs of medical training, while at the same time reflecting the growth and development of innovations in pedagogy, research, and clinical care.

The author deftly describes how, as medical education evolved from the didactic curriculum of the nineteenth century to the more experiential style of the twentieth, medical school facilities morphed from those containing large auditoriums and anatomical theaters to contemporary ones incorporating laboratories and clinical sites. To illustrate, Carroll focuses on nine representative medical colleges, reflecting a geographical spectrum or particular ethnic identity, demonstrating the major developments in medical school design, while illustrating how their design principles ultimately promoted their goal, as she expresses it, of producing the “modern physician.”

There are five chapters, each devoted to a distinct aspect: Chapter 1 addresses the American transition from the nineteenth century, European style, multistructure “institute” to the single building containing dedicated “wings” devoted to the various disciplines of preclinical scientific study, including anatomy, physiology, pathology, and biochemistry. Chapter 2 describes the movement toward closer integration of preclinical and clinical work, stimulated by the Flexner Report and the AMA’s Council on Medical Education. In Chapter 3, the author explores the influence of major architectural firms devoted particularly to medical school design and the role of philanthropy, including John D. Rockefeller’s General Education Board (while acknowledging discriminatory practices that favored elite research schools attended primarily by white men and disfavoring Black medical colleges and women’s schools.)

Chapter 4 describes the efforts to gain community support and to expand opportunities to underrepresented scholars. It is here that the author quotes MHSNJ’s own Steven Peitzman, himself a serious devotee of medical school architecture, emphasizing the important role played by the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in promoting medical education for women. Chapter 5 is devoted to the growth and development of residential medical colleges and the movement toward inclusion of related professional schools, including nursing, dentistry, and pharmacy.

An epilogue collates information presented in the previous chapters and reinforces the concept that pedagogy continues to shape medical training, research, and patient care. All of the material is richly illustrated and extensively annotated and there is a comprehensive bibliography.

Far from being pedantic or abstruse, Carroll’s study is interesting and insightful. Peitzman’s dust jacket blurb is illuminating: “[The author’s] lucid prose and ample illustrations reveal how changing notions of training physicians and creating knowledge shaped the buildings—and how buildings in turn honed the contours of curriculum.”

1 The New York Times, April 15, 2023, page B4