Founded in 1980 |

|

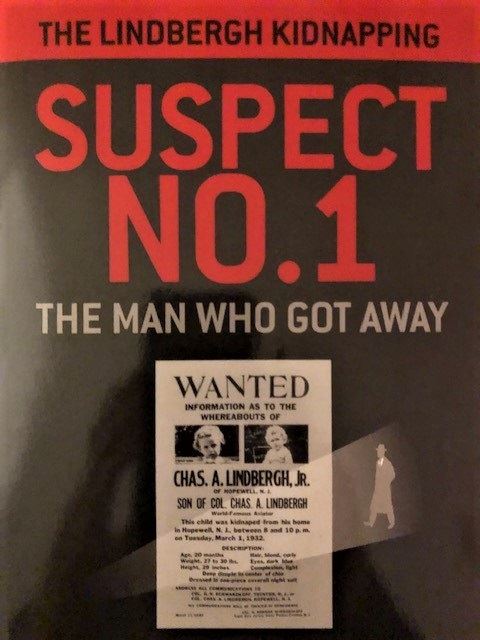

| Lise Pearlman, The Lindbergh Kidnapping Suspect No. 1: The Man Who Got Away,(Berkeley, California: Regent Press, 2020). |

Reviewer: Vincent J. Cirillo, PhD

September 26, 2020

Since the mid-1970s, numerous revisionists have sought to exonerate Bruno Richard Hauptmann of the kidnapping and murder of Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., the 20 month-old child of the famous aviator and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Subsequent conspiracy theories have seen Colonel Lindbergh evolve from victim to suspect, from hero to villain. In their 1993 book, Crime of the Century, co-authors Gregory Ahlgren and Stephen Monier claimed that Lindbergh killed his own son accidentally when one of his sadistic practical jokes went awry. The authors presented no hard evidence to support their charge and, in fact, confessed, “There is no smoking gun here.”1

In Lise Pearlman’s Suspect No. 1, revisionism has been transmogrified into full-fledged conspiracy theory. She asserts that, with malice aforethought, Colonel Lindbergh deliberately murdered his own son to harvest the toddler’s internal organs for scientific experiments, orchestrated a phony kidnapping to hide the truth, and then usurped command of the police investigation to railroad an innocent man into the electric chair.

Dr. Alexis Carrel of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in Manhattan was a real life Jekyll and Hyde. On the one hand, he was a lifesaving surgeon who won the 1912 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his brilliant work in vascular suturing and organ transplantation, and on the other, a life-damning fanatical eugenicist. Especially dangerous was Carrel’s belief that to create a superior race, misfits – even sickly infants – had to be eliminated from the gene pool. The eugenic ideas advanced in Carrel’s non-fiction bestseller, Man, the Unknown (1935; German edition 1936), foreshadowed and fueled Hitler’s Final Solution. Lindbergh met Carrel in November 1930 and over time, the latter exercised “tremendous influence” over the Lone Eagle, “not all for the good.”2 While deeply impressed by Carrel’s vision, Lindbergh did not share the Frenchman’s zeal for such radical theories as euthanizing people with disabilities by gassing.

Lindbergh and Carrel supposedly concocted a plan whereby Lindbergh would hand off his sedated son on March 1, 1932 to unnamed accomplices, who would then deliver the child to the Rockefeller Institute’s satellite laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey, located fifteen miles from Lindbergh’s home, in Hopewell. There, Carrel would harvest the boy’s internal organs for their experiments in organ culture, utilizing the revolutionary perfusion pump invented by Lindbergh. Pearlman writes, “Lindbergh might well have felt like Abraham offering the Almighty his son Isaac – not to the Biblical God but to the God of Science with Carrel as the chosen instrument” (p. 391).

“Motive is the Achilles heel of bogus true crime books.”3 Lindbergh’s motive, Pearlman opines, lay in his embrace of eugenics, insinuating he could not abide siring an imperfect child. The “Little Eaglet’s” imperfections are described in the book as an oversized head (hydrocephalic?), an unclosed anterior fontanelle, and overlapping toes. Actually, Little Charlie was a handsome boy with blue eyes and a crop of golden curls, was tall for his age, swaggered about, in Anne’s words, “on his firm little legs,” and was possessed of a remarkable vocabulary indicative of normal mental development. Rather than portend hydrocephalus, the delayed ossification of the fontanelles is a known consequence of rickets, a vitamin D deficiency, for which Little Charlie was being treated with viosterol (synthetic vitamin D). At the time, rickets was common in the United States among children under four years of age, regardless of family income.

A few months before the kidnapping/murder, Anne had written to her mother-in-law: “C. Jr. and Sr. have a wonderful time together [playing pillow fights];” “[C.] was quite proud of him;” “[C.] began to take such interest in the baby – playing with him, spoiling him by giving him cornflakes and toast and sugar and jam off his plate in the morning and tossing him up in the air. After he’d done that once or twice, the boy came toward him with outstretched arms: ‘Den!’ (Again!);” “C. admits the boy is ‘good-looking’ and ‘pretty interesting.’”4 Lindbergh called the boy “Buster” every time he saw him – a term for a rough and tough kid, not a congenital weakling. This does not sound like a man who so despised his offspring as to sacrifice his life a couple of months later to the “God of Science.”

After rehashing what is known about the Lindbergh kidnapping case in the first 390 pages of the book, the author’s assertions are finally revealed in a chapter titled “Reconstructing the Crime.” This thesis should have appeared at the beginning, so that Pearlman could have clarified along the way which information had supporting evidence, which was reasonably assumed, and which was purely conjectural. Some of Pearlman’s most outrageous statements -- with zero corroborating documentation – are as follows: “Carrel suggested to Lindbergh that one of the first human sacrifices in the perfusion device be Lindbergh’s son” (p.391); “Lindbergh and [his lawyer Henry] Breckinridge hit upon the idea of a fake kidnapping . . .” (p. 391); “Lindbergh purposefully made sure Skean [a Scottish terrier that slept under the toddler’s crib every night] was left elsewhere at either Englewood or a Princeton kennel” (p. 394); and “It was Lindbergh’s plan all along to have the corpse found at some point to put an end to the convoluted ransom scheme” (p. 399). Clearly, every statement above is based on conjecture, not hard evidence. Pearlman admits that no one witnessed Lindbergh hand off the toddler to his accomplices (p. 395). In short, as was the case with Ahlgren and Monier, “There is no smoking gun here.”

In a number of instances, Pearlman’s interpretation of factual events can be construed otherwise. For example, she views the cremation of the toddler’s remains soon after autopsy as an obstruction of justice, implying that Lindbergh acted to destroy incriminating evidence and clues. An equally rational, but far less sinister, interpretation is that the body was cremated to prevent souvenir hunters from desecrating Little Charlie’s grave.

Even though Lindbergh has fallen from grace because of his antisemitism, his sympathy for the prewar Nazi regime, and his fathering of five children with two women out of wedlock, I venture to say that Pearlman’s ghoulish hypothesis will be a hard pill to swallow for most readers. It is simply too fiendish, as though Lindbergh and Carrel “had been obscene demons, marketing the corpse itself.”5

1. Gregory Ahlgren and Stephen Monier, Crime of the Century: The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax (Boston: Branden Books, 1993), p. 202.

2. Walter S. Ross, The Last Hero: Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), p. 242.

3. Jim Fisher, The Ghosts of Hopewell: Setting the Record Straight in the Lindbergh Case (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999), p. 96.

4. Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1929-1932 (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973), pp. 204, 224, 225.

5. Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas (London: Chapman & Hall, 1843). Facsimile Reprint. New York: Columbia University Press, 1956, p. 135.