Founded in 1980 |

|

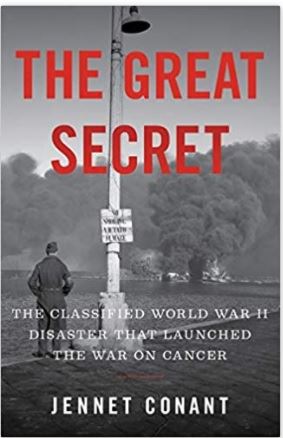

| Conant, Jennet , THE GREAT SECRET: The Classified World War II Disaster that Launched the War on Cancer. New York: W. W. Norton, 2020. ISBN: 978-1-324-00250-5. |

Reviewer: Michael Nevins, MD |

Historian Jennet Conant’s new book, The Great Secret, will be of special interest to MHSNJ members, because its hero is one of our own, Dr. Stewart Alexander (1914-1991.) I should know, because I’ve always viewed Stewart as my own medical mentor; among other things, he encouraged me to join the MHSNJ and together we presented a paper at our fledgling organization’s second meeting. Stewart was born and raised in Park Ridge in Bergen County and practiced internal medicine and cardiology in his hometown for decades. He supplanted his father, Samuel, who had served as president of the Medical Society of New Jersey; Stewart was president of the Academy of Medicine of New Jersey. When he retired, because of poor health, it ended a three-generation, 117-year practice that dated back to 1865. But what does any of that have to do with Jennet Conant’s book? The answer is hinted at in the book’s subtitle: The Classified World War II Disaster that Launched the War on Cancer. What disaster? On December 2, 1943, the German Luftwaffe made a surprise air raid on the Italian port city, Bari. Seventeen allied ships were sunk in the harbor, over a thousand servicemen and hundreds of civilians were killed, and only Pearl Harbor was a greater calamity. In subsequent days, many servicemen were dying with mysterious symptoms and some suspected that Nazi bombs might have contained poison gas. The 29 year-old Lt. Col. Alexander, who had done research on mustard gas at the Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, was dispatched by General Eisenhower to investigate. I won’t reveal any more, other than to say that our hero discovered that, indeed, the cause of many deaths was mustard, but that it came from 2,000 bombs secretly stored in an American Liberty ship. Moreover, postmortem examinations revealed profound damage to lymphatics and marrow and Alexander appreciated that, in peacetime, this toxic effect might prove useful to treat certain malignancies. That’s hardly the end of Conant’s thrilling account, but you’ll surely want to read it yourself and learn why none other than Winston Churchill threatened to court-martial our colleague, Stewart, if he publicly revealed his findings. Jennet Conant is a marvelous storyteller, but she also has a unique advantage: her beloved grandfather, James Conant, was intimately involved with many of the events that she describes and she had personal access to materials unavailable to others. Indeed, James Conant had been engaged in mustard gas research during World War I and, in addition to his distinguished career as Harvard’s president, he co-led the Manhattan Project and served on the founding Board of the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute. Not only has Jennet written a biography of her “warrior-scientist” grandfather, but she has also authored other books about such notables of the era as J. Robert Oppenheimer, Alfred Loomis, Roald Dahl, and Julia and Paul Child. She has a gift for character analysis and along the way we gain insight into the complicated personalities of such luminaries as Milton Winternitz, Cornelius “Dusty” Rhoads, and Alfred P. Sloan. No doubt I’m prejudiced, but I’m certain that anyone interested in medical history—and surely any member of MHSNJ—will be entranced by this “page-turner.” It’s bound to be a best-seller and award winner. |