Founded in 1980 |

|

|

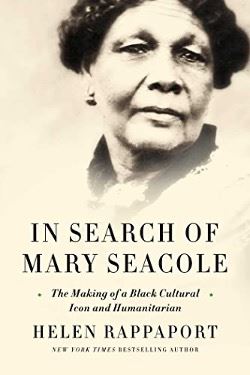

Helen Rappaport, In Search of Mary Seacole: The Making of a Black Cultural Icon and Humanitarian New York, Simon and Schuster (Pegasus Books), 2022, 416 pages ISBN 978-1639362745 |

Reviewer: Richard Marfuggi, MD FACS DMH / November 13, 2022

I believe that a proper review of this book requires a discussion of the author as well as her subject. Anyone who has done medical history research knows how fraught the process can be in this age of Wikipedia. While it may be easier to get and disseminate information than ever before, it requires significant effort to determine if that information is accurate. Compounding the problem of accuracy is the intrusion of myth and legend.

Dr. Helen Rappaport is a historian specializing in the period 1837-1918 in late Imperial and Revolutionary Russia and Victorian Britain. She received her doctorate in Russian Special Studies from Leeds University.

Throughout the book, Rappaport describes the many blind leads and countless inaccuracies she encountered during her twenty years separating the informational wheat from chaff. This is, in a sense, a book within a book as the reader comes to know both author and subject.

It is difficult to give sufficient credit to Mary Seacole, née Grant (c. 1805-1881) for her contributions to humanity and to the field of medicine. Though known in her own time, her renown faded after death. Rappaport’s book restores Seacole’s place in the history of medicine as well as her status as a cultural icon and humanitarian.

Seacole was born in Jamaica to a mixed-race freed woman and a Scottish soldier. While ever proud of her Scottish heritage, she learned homeopathic medicine from her mother. In addition, Seacole’s mother was an entrepreneur who ran a successful boarding house and Mary followed suit, becoming an astute businesswoman herself.

Marriage to a West India Company employee lasted ten years until his death. She then ran lodging houses (which often included convalescent centers) and restaurants in Jamaica and Panama. Her medical skills proved invaluable for treating cholera patients during epidemics as well as localized outbreaks in both countries. Some patients became lodgers, while others were treated in her makeshift clinics. She offered care to anyone in need, irrespective of their ability to pay.

Seacole learned of the work of Florence Nightingale in Crimea. Being a proud citizen of the Empire and having already demonstrated her abilities caring for wounded and sickened soldiers, Seacole offered her homeopathic services to the British military. Her offer was refused.

Seacole seldom took no for an answer. Accordingly, she paired with a Panamanian businessman and opened a store, restaurant, and medical clinic in Balaclava. (Balaclava was a settlement, now a district of the Ukrainian city of Sevastopol, on the Crimean Peninsula.) In contrast, Nightingale and her staff performed their ministrations at a much safer distance from the front lines.

Sadly, one of the major opponents of Seacole’s work was Nightingale who resented the fact that Mary had no “formal” training in nursing or medicine. Nightingale also resented the accolades and medals heaped upon Seacole by the British press and multiple heads of state.

After the war, Seacole endured many financial setbacks. She wrote a best-selling memoir but even that did not sustain her. As the veterans of the Crimean War died, so did the memories of her good deeds. She died in relative obscurity.

Even though they never met, because it was deemed inappropriate for a monarch to receive a subject of mixed blood, Victoria was an admirer of Seacole.

Not until 2016, was Seacole publicly recognized with a statue in the gardens of St. Thomas’ Hospital (Lambeth, London). The impressive work stands 16 feet tall and is inscribed with a quote from her autobiography, “Wherever the need arises on whatever distant shore I ask no higher or greater privilege than to minister to it." Seacole's statue is generally considered to be the first in Britain to recognize a named black woman. (To the chagrin of some, the statue of Nightingale erected in 1915 at Waterloo Place stands just over 9 feet.) In a final twist, Rappaport discovered a portrait of Seacole, previously thought to be lost, that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

When an amazing subject is rediscovered by an untiring and dedicated author, the result is a major contribution to medical history.

Richard A Marfuggi MD FACS DMH

November 13, 2022

Mary Seacole statue, St. Thomas’ Hospital, Lambeth, London National Archives of the United Kingdom |

Mary Seacole, Nurse, adventurer and writer By Albert Charles Challen (1847–81), National Portrait Gallery, London |